Online webinar event hosted by Terri Janke and Company, delivered Monday 29 July 2024

Part One – Recount and reflect on the webinar

Earlier in 2024, I was pleased to be among the attendees present during an online webinar hosted by Terri Janke and Company, and presented by Anika Valenti, a Senior Associate in the firm. The webinar was relevant to Indigenous producers working in the bushfoods industry, to provide them some background and knowledge about the laws and regulations that apply to that industry. The session provided a high-level discussion about the legal considerations that bush food producers and related enterprises need to know when they develop their business venture. The webinar also offered important tips for Indigenous producers to protect their Indigenous Cultural Intellectual Property (ICIP) and their IP more broadly. All images contained in this blog post are from the presentation slides shown during the “Law Way: From Bush to Business” webinar, and are the work of Terri Janke and Company Pty Ltd.

It was a rich and valuable opportunity to understand the legal and regulatory considerations that apply to the Native Food sector, and what those mean – either by their absence or their presence – for the protection of Indigenous cultural practice. Some of what was presented in the webinar covered information I had previously encountered while researching and writing parts of a report produced by the RMIT Blockchain Innovation Hub and commissioned by Agriculture Victoria, as part of their current exploration of the ways blockchain-based technologies might be applied within the context of the Victorian Native Food Fibre and Botanicals sector.

I have not previously published work based on those learnings or on other knowledge I have gained from related research work I have undertaken. So, as a starting point I will use this post (Part One) to recount and reflect on what I learned during this webinar, and Part Two which will likely be shorter, will include my reflections about points raised during the presentation and the Q&A discussion that I found highly interesting and relevant to my overall research.

Building out from this, I will use this post as a catalyst for branching out and connecting or linking to subsequent posts that, in their aggregate, will constitute a deeper and more extensive research translation project that reflects the connections in knowledge that I have made in my readings and explorations of other sources that I have encountered and consider to be relevant, pertinent and of profound significance.

The Native Food and Botanicals sector is growing, significantly and rapidly.1 Yet, only fifteen percent of the industry is Indigenous-owned (according to data that relies on the voluntary disclosure of Aboriginal identity…). The Indigenous participation rate within the sector counts at a mere 1-2 percent, and that participation is predominantly represented at the farm gate, and does not extend further into the supply chain. This indicates an issue for Indigenous representation in the sector, primarily because the market activity that occurs after the farm gate is where the majority of the profit margin and – therefore economic activity and wealth building – exists.

The industry, according to Janke and Co, is challenged by “a need for real leadership” (or a lack of it, which I interpret as encompassing meaningful advocacy, resourcing, regulation and so forth), and by rampant misappropriation of Indigenous Knowledge (IK) and ICIP. For example, the presentation stated that Mary Kay (a well-known cosmetics enterprise) uses Kakadu Plum in some of their products, with Kakadu Plum being a plant that yields (apparently) the highest level of Vitamin C. Yet, the benefits derived from their use of that Indigenous plant do not flow back to the community, either in a financial sense or in ways that would otherwise benefit the community.2 Another challenge highlighted in the webinar is the issue of biopiracy, where knowledge about culturally-derived plants and their properties is claimed by non-Indigenous entities, yet there is no flow-back of benefits to the community from whom the claimed knowledge or genetic materials is derived.

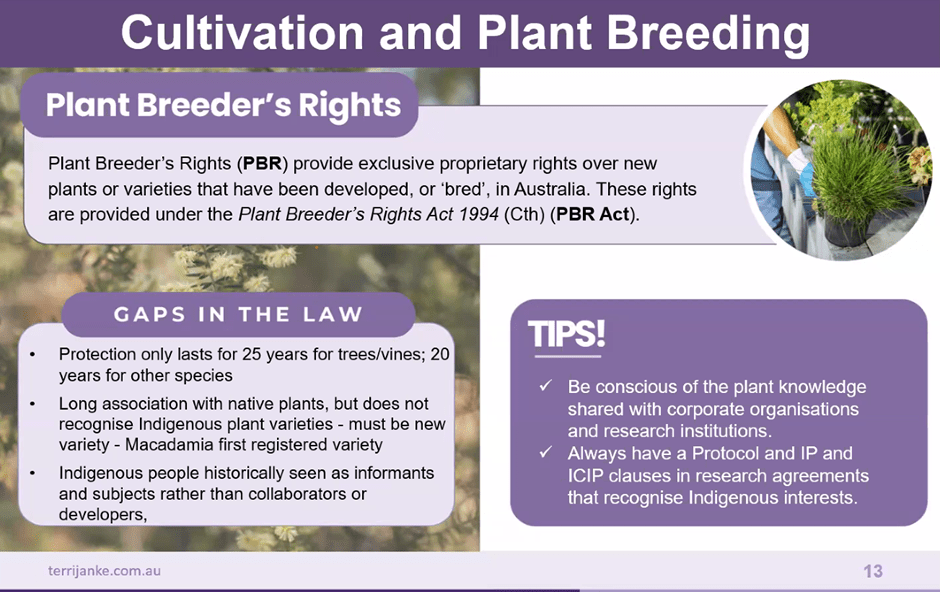

The above slide highlighted the concept of Plant Breeder’s Rights, in order to offer a warning of sorts about how to protect Indigenous IP from organisations who, armed or at least safeguarded by this legislation and the unsuspecting and therefore permissive communities who unwittingly grant access, can come in on Country, take samples of plants etc and from those samples they are able to develop new varietals, which do not come under the protection of ICIP that might be applied to the original sample. In this way, the benefits derived do not have to flow back to the community or communities from whose lands those samples were taken.

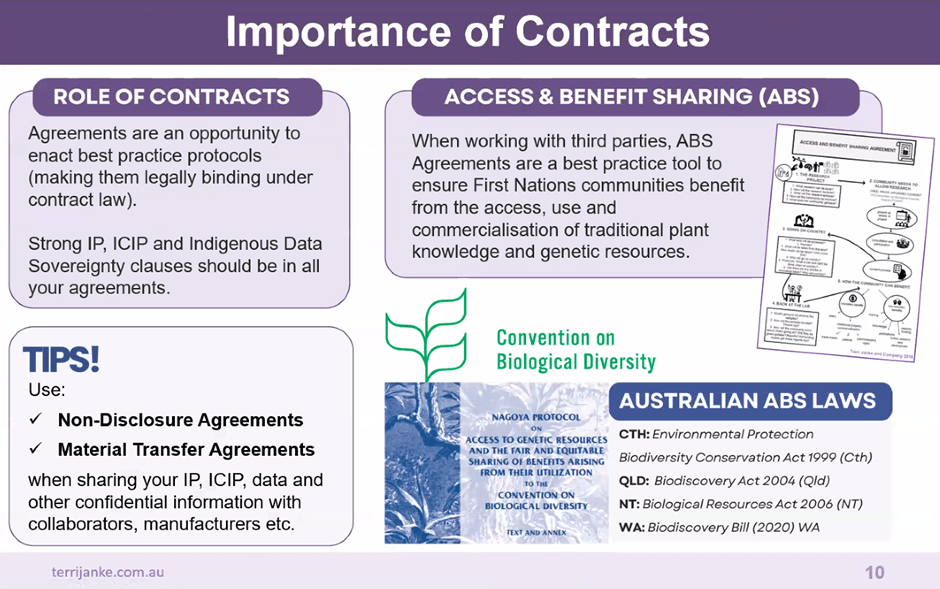

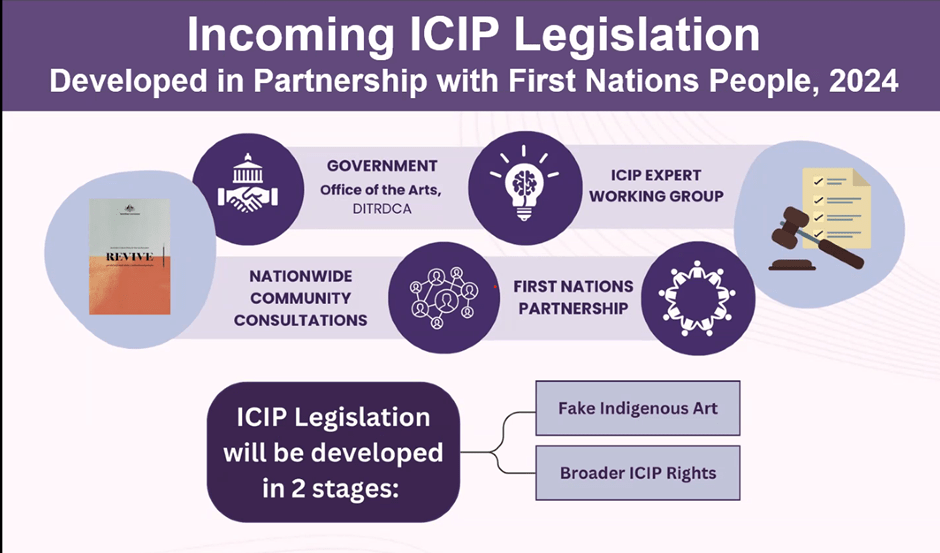

Some of the strategies that were suggested in the presentation as potential solutions for overcoming the challenges currently being faced by the bushfoods sector included the introduction or application of Intellectual Property (IP) and Access and Benefit Sharing Regulation (ABS) as far as they can be applied. It was stated at this point in the session that ICIP is not currently adequately protected by Australian Law.

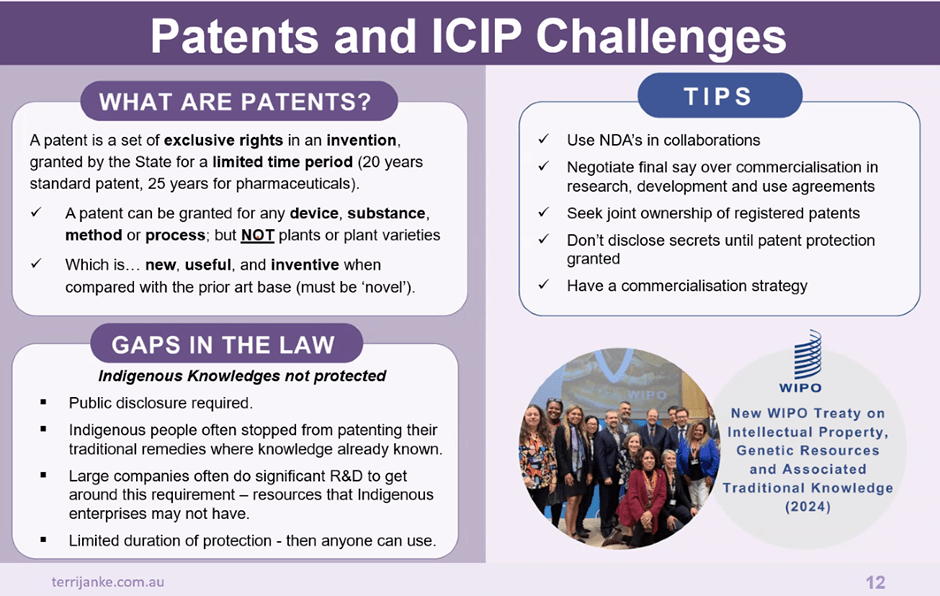

In light of this current inadequacy in the protection of Indigenous cultural heritage, the webinar outlined the use of patent registrations and how they can be applied. While a plant or a seed, (thankfully) cannot be registered under a patent, what can be registered are capabilities of those resources insofar as what can be extracted from them and then used for other products e.g. in the previously-mentioned Mary Kay example, Kakadu Plum and the property or capability that can be extracted from it (Vitamin C), and then used in one of their cosmetic products. What can also be registered under a patent is a process (this might be a harvesting, extraction, preparation or other novel process), a particular attribute of the resource (the enzyme for example) and an application that has a particular quality (e.g. – numbing quality derived from a particular application etc.).

What this highlights, however – as can be seen in or inferred from the text within the above image (see “Gaps in the law”) – are problems for cultural safety and protection that are inherent in this system. For example, the registration of a patent requires public disclosure of a particular process, which, within the purview of Indigenous cultural practice, may be inappropriate or unsafe – and, after the conclusion of the limited duration of protection, open to be used and commercialised by others. All aspects of cultural knowledge are considered sacred, however some are traditionally regarded as being highly sensitive or even secret and according to Aboriginal Law, are only appropriate for sharing with those who carry cultural authority that is gained through totemic or kinship assignment and after reaching certain stages of ritual or ceremonial standing. Other significant barriers to Aboriginal enterprises in this regard stem from the prohibitive expenses and human resourcing that may be involved in conducting the research required to isolate a particular enzyme (for example) that can then be registered under a patent.

One recent positive step toward protection of Indigenous knowledge came about in May 2024, when the 193 member states of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) approved by consensus a new global treaty related to intellectual property (IP), genetic resources and associated traditional knowledge. The treaty, once it is enforced, will establish in international law a new disclosure requirement for patent applicants whose inventions are based on genetic resources and/or associated traditional knowledge. When a claimed invention in a patent application is based on genetic resources, applicants will be required to disclose the country of origin or source of those genetic resources. Where the claimed invention in a patent application is based on traditional knowledge associated with genetic resources, applicants will be required to disclose the indigenous peoples or local community who provided the traditional knowledge.

In the meantime, as can also be seen in the above image, what can be applied by Indigenous communities and enterprises is contractual in nature, for example the use of non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) or commercial agreements that outline use of Indigenous knowledge and how the relevant community will be honoured and, ideally, provided final say within those agreements. The advice for participants was “Don’t pass on knowledge to anyone until you have an NDA in place. This can protect you until formal agreements are in place.” And in the instances where commercial organisations or university and other research institutions are involved, Access and Benefit Sharing (ABS) agreements will protect your community while testing and resource collection is occurring to determine what will happen to materials and the knowledge and findings etc that result from the use.

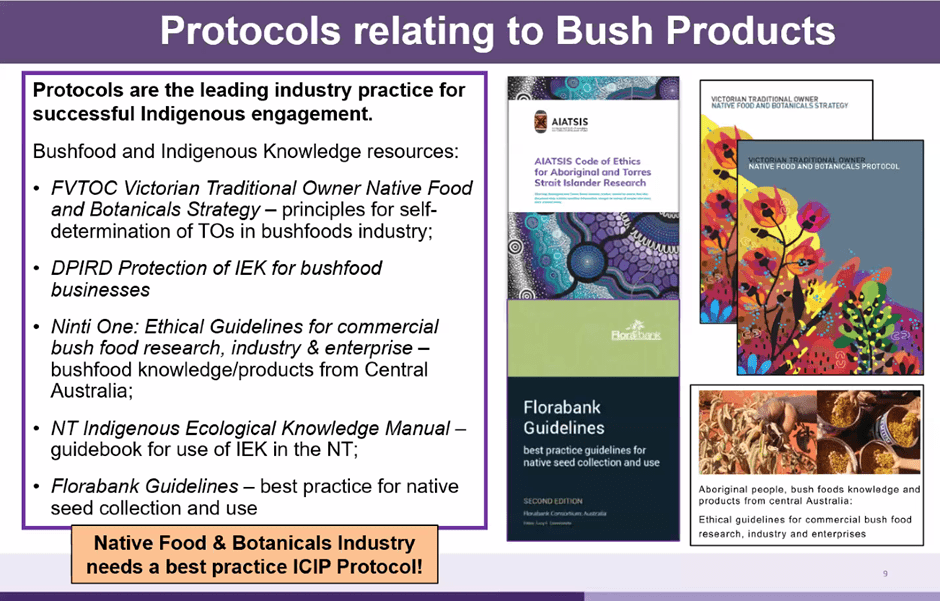

Another strategy comprises the use of protocols, as they stated best practice protocols can go beyond the law. These protocols provide the frameworks that enable people to draw up contracts and then pursue breaches of contracts when they occur. The presenter strongly recommended that all businesses should be developing their own protocols, stressing that it is vitally important to have things written down and protected, and that this is how protocols are made legally binding. One scenario might apply to the example of an Indigenous tour guide who wants to stipulate what the protocols are for their participants. One form of protocol that can be enforced in the event of a breach is a participant release form – as long as people sign on the dotted line. Such a document will include terms and conditions outlining what is acceptable, perhaps by way of a list of what tour participants can and cannot do. For example: Taking photos of plants and recording the knowledge or processes associated with their use and so forth. Stories and songs or other intangible heritage may be prohibited from being recorded or reproduced. If a participant is taking notes or producing maps or artworks or so forth, the tour guide can request that the copyright of the information is assigned to them.

The Native Food and Botanicals Sector is a highly regulated industry. To classify a product and sell it to consumers as medicine or medicinal requires legally certified permission. This was described as a lengthy and very expensive process, which may include meeting requirements to gain approvals for licences and permits granted by the TGA; ACCC; AICIS; IP bodies; FSANZ; and for meeting federal, state and local obligations and requirements pertaining to Privacy and Confidentiality, and licences for selling and harvesting. Thus, any product that is not tested and approved by the industry standards regulatory bodies must not claim to be medicinal in any way. To do so is illegal and enterprises making such claims can be prosecuted for doing so. (We will return to the conversation about what qualifies as medicine, who is qualified to use the term and what this means culturally later in the discussion where I will reflect on points raised during the Q&A session.)

So, what is ICIP anyway?

Put simply, as I understand it, ICIP applies to the thing (tangible or intangible) that is being protected, whereas ICIP Rights are the rights that are assigned to the right-holder in relation to the thing or process, knowledge, etc that is being protected.

Indigenous Cultural Intellectual Property (ICIP) is a branch of Intellectual Property law that gives legal protection to some of the things that are produced as a result of the intellectual efforts of Indigenous Australians.3 It covers tangible and intangible aspects of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ cultural heritage. Terri Janke, (namesake of the company who hosted the webinar) who is an international authority on Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property (ICIP) states that intellectual property law “gives people – creators – rights to property of their mind.”

ICIP includes ‘cultural practices, resources and knowledge systems developed, nurtured, and refined by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and passed on by them as part of expressing their cultural identity.’ (CSIRO)

It comprises ‘all objects, sites and knowledge, the nature and use of which has been transmitted or continues to be transmitted from generation to generation, and which is regarded as pertaining to a particular Indigenous group or its territory. This cultural heritage is a living concept that can be adaptive and includes objects, knowledge, literary and artistic works which may also be created in the future based on that cultural heritage and includes:

- literary, performing and artistic works (including songs, music, dances, stories, ceremonies, symbols, languages and designs)

- scientific, agricultural, technical and ecological knowledge (including cultigens, medicines and phenotypes of flora and fauna)

- all items of movable and immovable cultural property (including sacred and historically significant sites and burial grounds) and ancestral remains; and

- documentation of Indigenous Peoples heritage in archives, film, photographs, videotape, or audiotape and in all forms of media.4

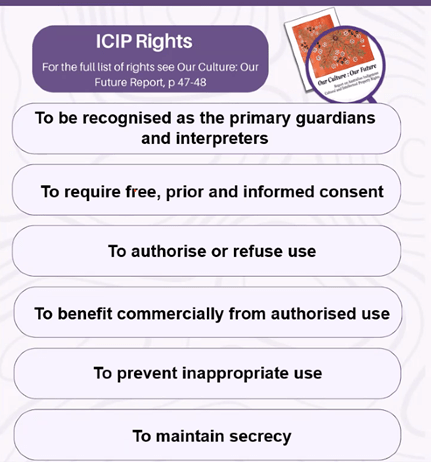

The rights to ICIP (‘ICIP Rights’) refer to the specific legal recognition that is consistent with principles of The United Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), endorsed by Australia in 2009, that gives effect to assigned rights that enable Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island peoples to:

- own, control and maintain their ICIP

- ensure that any means of protecting ICIP is based on the principle of self-determination

- be recognised as the primary guardians and interpreters of their cultures

- authorise or refuse the use of ICIP according to their own law

- in the case of secret Indigenous knowledge and other cultural practices, maintain that secrecy

- guard the cultural integrity of their ICIP

- be given full and proper attribution for sharing their cultural heritage

- control the recording of cultural customs, expressions and language that may be intrinsic to cultural identity, knowledge, skill and teaching of culture, and

- publish their research results.5

This definition, consistent with UNDRIP principles, is distinguished from the much narrower legal meaning in relation to a decision to “protect” something under IP laws.

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) is an international legal instrument that Australia is a signatory to. The presentation suggested that the following three articles are especially relevant in respect to ICIP and to the native food and botanicals sector in particular:

- Article 3 Indigenous peoples have the right to self-determination. By virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.

- Article 19 States shall consult and cooperate in good faith with the indigenous peoples concerned through their own representative institutions in order to obtain their free, prior and informed consent before adopting and implementing legislative or administrative measures that may affect them. (Cynical internal thought running through the mind of the author at time of writing: “Didn’t we all see how that worked out in reality.” -_- See the Northern Territory National Emergency Response, commonly known as “The Intervention”.)

- Article 31 1. Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions, as well as the manifestations of their sciences, technologies and cultures, including human and genetic resources, seeds, medicines, knowledge of the properties of fauna and flora, oral traditions, literatures, designs, sports and traditional games and visual and performing arts. They also have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their intellectual property over such cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions. 2. In conjunction with indigenous peoples, States shall take effective measures to recognize and protect the exercise of these rights.

The right, described in Article 31, for Indigenous peoples to maintain, control, protect and develop their cultural knowledge and heritage and IP includes instances where a commercial enterprise or a university research institution comes to work with them and their knowledge.

Other aspects that were covered in the final part of the webinar included the importance of developing and then safeguarding brands through the use of trademarks, what is considered ‘trademarkable’, registration of websites and other online materials and assets, and a gloss-over that touched on other legal obligations including fair trading, Australian Consumer Law, and a host of other considerations and requirements related to product safety and manufacturing, food preparation, licences, insurance, codes of conduct, employment standards, and OH&S.

Part Two will follow “shortly”, and will be based on a point raised during the Q&A discussion that I found interesting, sparking (for me) a connection to work that I have been thinking about in the course of my research: how terminology – words can be used to diminish Aboriginal culture.

It will also consider an issue raised during the presentation and how one aspect of blockchain might be used to resolve the challenge.

- According to studies and market analysis of the sector which estimated its current total retail market value and forecast projections for its growth on the basis of this data, it is anticipated that the sector will increase in value by 440 percent in ten years. This analysis is based on data gathered across four decades, and based on only thirteen species identified as “key” or “priority” species. There are more than 6,500 types of native food in Australia, and the above thirteen species are the only ones that have thus-far been certified by Food Standards Australian and New Zealand (FSANZ) and developed for local and international markets. ↩︎

- I interpreted the word “Community” in this context to mean relevant communities that would generally be defined as being the specific people or peoples from whom the cultural knowledge of the cultivation, harvesting and uses of the Kakadu Plum originated and who are also, I would assume, the Traditional Owners of the lands from which the original plants and their genetic properties were derived (prior to being cultivated elsewhere for example). ↩︎

- Arts Law Centre of Australia (2024). ‘Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property (ICIP)’, Arts Law, Information Sheets, Available at <https://www.artslaw.com.au/information-sheet/indigenous-cultural-intellectual-property-icip-aitb/>. Accessed 5 June 2024. ↩︎

- CSIRO (2024). ‘Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property Principles’, Last updated 29 May 2024. Available at <https://www.csiro.au/en/about/Policies/Science-and-Delivery-Policy/Indigenous-Cultural-and-Intellectual-Property-Principles>. Accessed 5 June 2024. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎