Digital Ethnography Research Center Showcase – Thursday, 22 October, 2020

In October 2020, I participated in the EPIC 2020 Graduate Colloquium, an opportunity for graduate student participants to share and get feedback on our research projects, to meet senior colleagues in related fields and industries, and to build a supportive cohort of fellow graduate students. There were amazing minds among us – it was a privilege to be among the talented cohort who came from universities all around the world.

The Colloquium was co-facilitated by Jay Hasbrouck (Pathfinder/Anthropologist at Facebook, Seattle, USA) and Annette Markham (Professor at Digital Ethnography Research Centre, RMIT, Australia) who guided our cohort through a three-day series of events in the week preceding the main conference. It was enriching to say the least. My key takeaways: “Meet people where they are” (in terms of digital ethnographic practice) and Writing in Snowflakes – an inspiring and motivating session facilitated by Professor Annette Markham. There were more than a dozen amazing sessions; I have roughly ten long OneNote pages of detailed notes.

The main conference explored the question ‘How do concepts of scale define the scopes, contexts, and impacts of ethnographic work?‘

I was given an opportunity to present my research as part of the Digital Ethnography Research Centre (DERC) Showcase, using a PechaKucha format. It was an excellent challenge – not only to boil down my work into 20 visual slides each at 20 seconds, but to think about my work in relation to Scale. The result is below – minus the video, which I don’t think needs to be attached [Originally posted in April 2021. Post edited in August 2024 to include images.]. In addition to the people I have referenced throughout, I reference ideas taken from my reading of Gregory Cajete, Leroy Little Bear, Christine Black, Arun Agrawal, David Turnbull, Mary Graham, Ghillar Anderson in Yunkaporta, and Clancy Wilmott. (20 seconds per slide didn’t afford me the luxury of Harvard referencing.)

Blockchain Mapping and Indigenous Knowledge Systems, Megan Kelleher

Let’s acknowledge the Woiwurrung and the Bunerong peoples – autonomous custodians of Country – for honouring their obligation to care for all entities within the unceded lands, skies and waters that made them, from where we now conduct our business. Let’s pay respects to the custodians of the lands where you are receiving this message.

I too am a custodian – of Baradha and Kapalbara country, a kaiyou from a matrilineal bloodline. Childhood relocation dislocated me from place and by extension identity. For that I’m threatened into the silence of assimilation. But I am always on Country, Goodithulla is my dreaming so I speak from this to pursue decolonisation.

My journey into womanhood, motherhood and an understanding of my role as the conduit of a bloodline that would have been eradicated if not for my ancestors’ adaptability and survival empowers me to resist assimilation. I retain my relatedness and uphold an autonomy without transgressing the autonomy of others.

I’ve lived in both worlds empowering me to codeswitch, and occupy what Bhabha calls a third space, to employ what Moreton-Robinson calls a ‘tactical subjectivity’ to dialogue from the inside and interrogate from the centre of this research with other Indigenous peoples – so I have chosen an Indigenist, participatory observation research method grounded in Indigenous Standpoint theory.

From this position I undertake this research into Indigenous Knowledge systems and how they guide and define Indigenous governance systems and processes. IK systems reflect the ecological, social and cultural contexts and systems in which they sit. This is an ontology grounded in place.

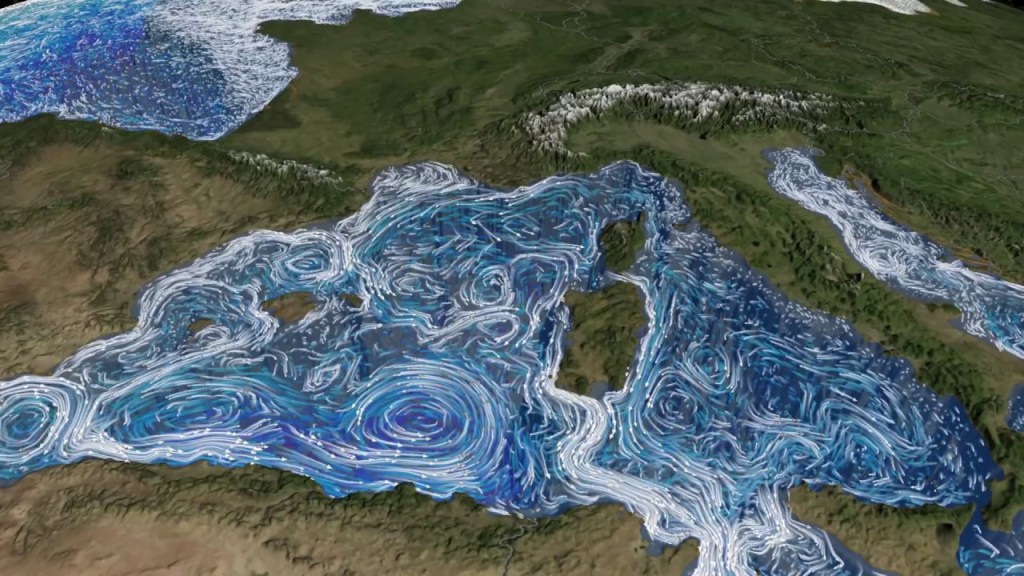

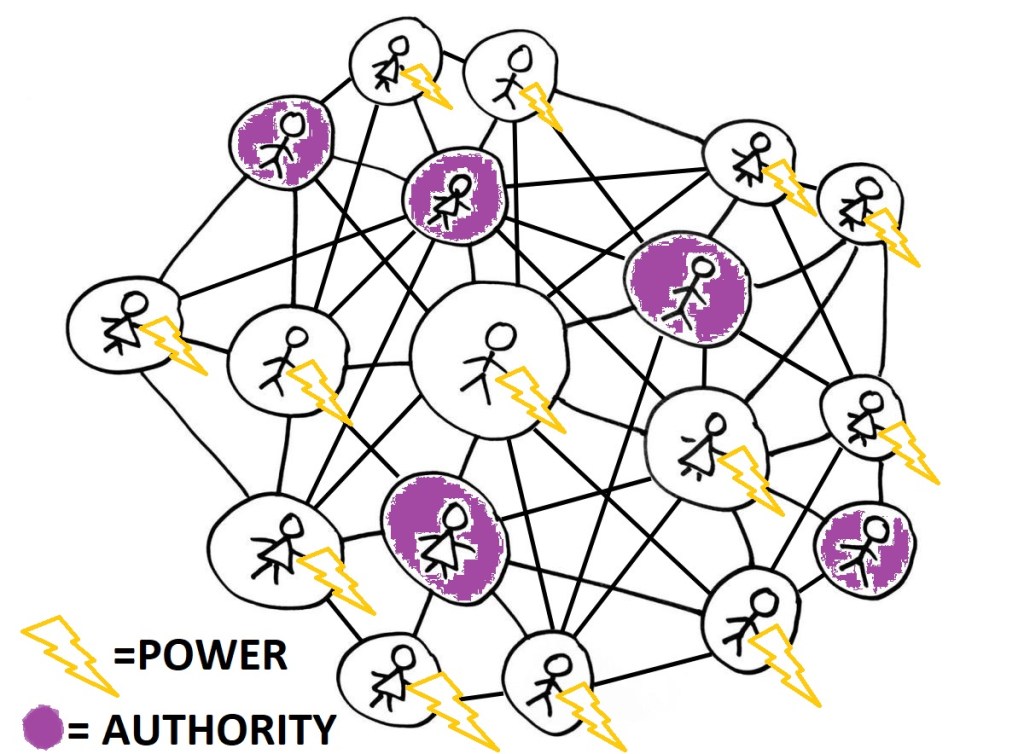

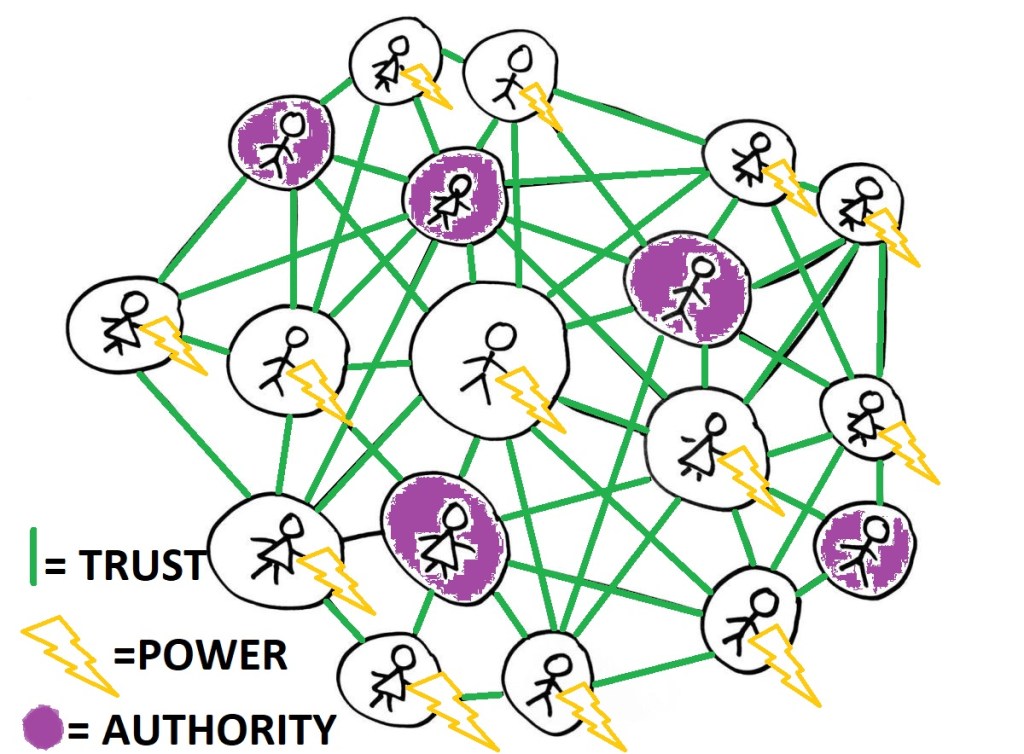

Where all entities are in relation and cannot exist unless in relation to something else. Therefore, the system is interconnected, interdependent, and relational. All entities within the system have knowledge, and the knowledge has value – sacred value. Therefore, governance is distributed among all entities in the system and is heterarchical. Humans are not in the centre, or at the apex.

Because these systems are in constant flux, IK constantly adapts in response to changing conditions in a dynamic, non-linear and self-organising process. Indigenous knowledge is process, and attempts to capture this knowledge decontextualizes it from time and place.

Because place – or land – is the source of all knowledge, and therefore the source of law. The land defines the processes of law – or the governance model – that exists within that place.

This is not simply a perspective, but a paradigm from which questions around governance can be posed in relation to the blockchain ecosystem.

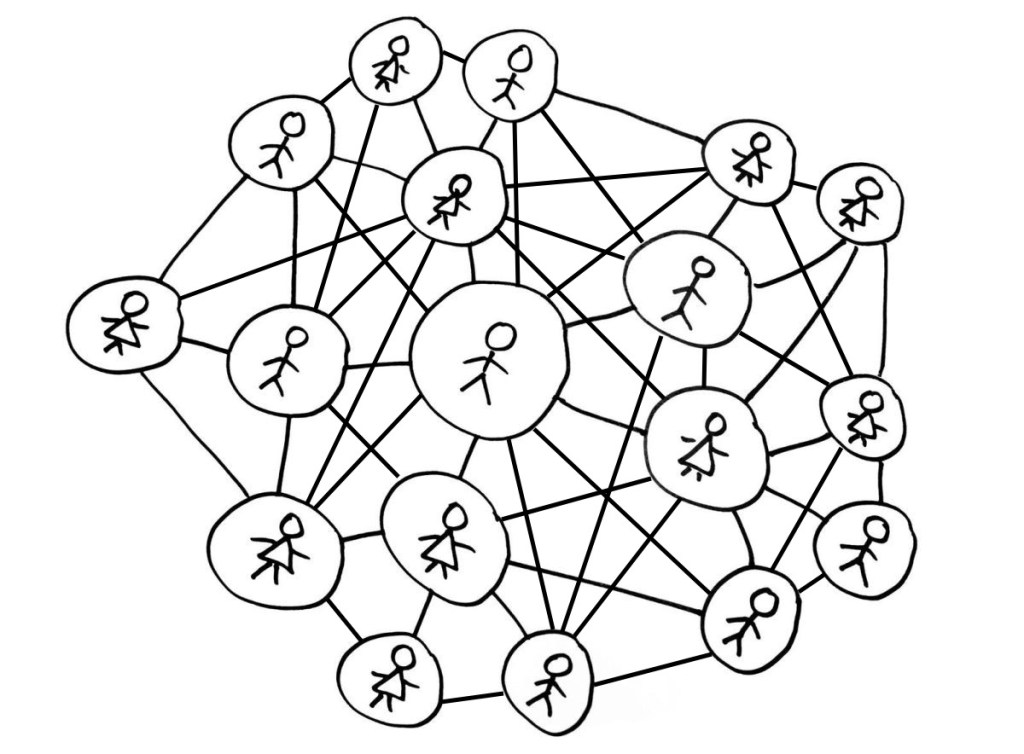

A blockchain is a distributed ledger, a record of value exchanges not controlled by a central authority. It’s like a database distributed across multiple computers located anywhere in the world and accessible to anyone with an Internet connection. Data is irreversibly added and updated in real-time under the consensus of all the nodes running the software in the network.

Kombu-merri academic, Dr Mary Graham describes Indigenous Governance as a type of multipolarity, gerontocracy and meritocracy. No central group, no hierarchy, no one group dominates other tribes. “They are all their own boss”, like “a country of all local governments that are all interdependent” and all autonomous.

Unlike in the West where power and authority are conflated, in Aboriginal governance, power and authority are separated. Authority is in the hands of knowledgeable older people – who have authority, but they don’t have power. Power is diffused throughout the group.

Trust is embedded in the network by virtue of the adherence to protocols outlined by kinship, relationality and obligation to place. In this model, trust is contingent on the separation of power and authority.

The value of Indigenous knowledge lies precisely in its local, place and practice-based character. Attempts at preserving it immediately decontextualizes it; renders it “a dead collection of facts”. Rendering it commensurable with scientific knowledge is to lose its cultural specificity. ‘…captured’ knowledge … is not definitive, but rather a snapshot in time.’

Turnbull suggests ‘one way in which differing knowledge traditions can interact and be mutually interrogated is by creating a database structured as distributed knowledge and emulating a complex adaptive system’.

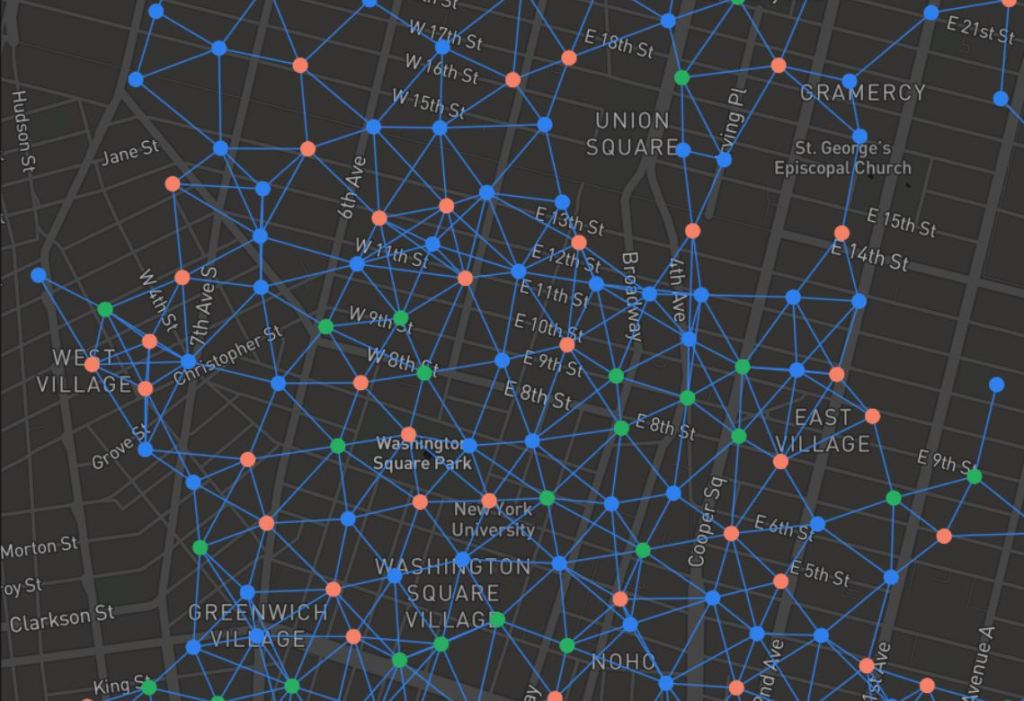

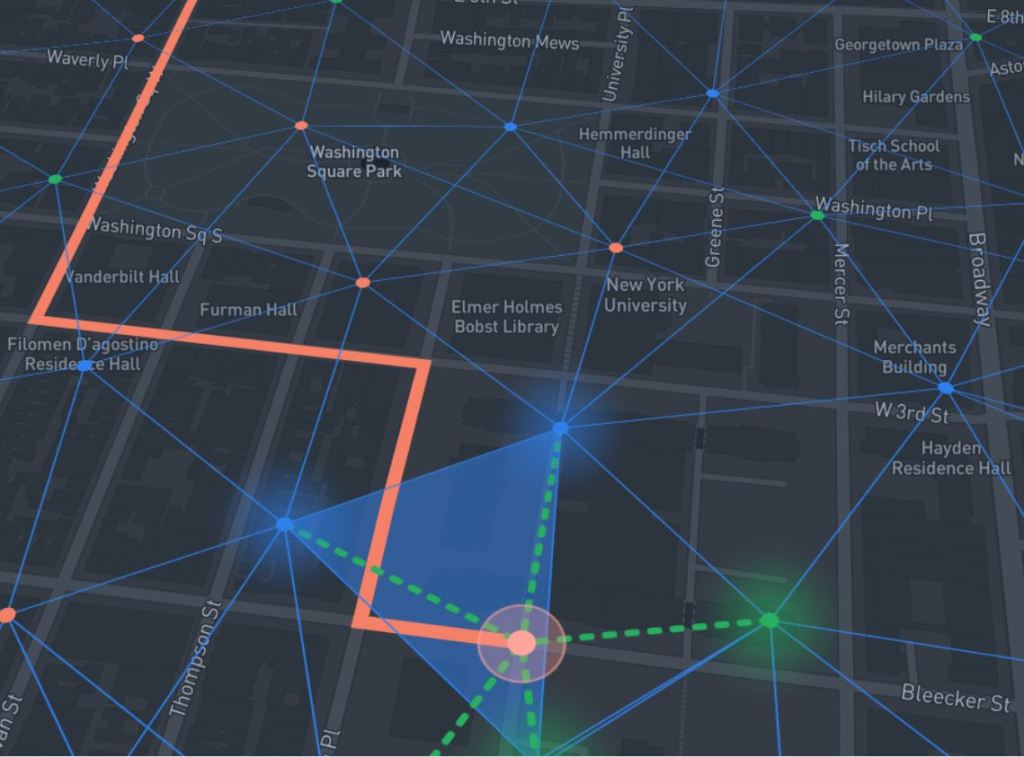

Rather than attempt to capture a snapshot of knowledge in time, this project is investigating whether a distributed blockchain-based map that is actively evolving and contestable – using the example of FOAM, a distributed, Blockchain-based mapping application – might ‘emulate a complex adaptive system’. Can blockchain technology emulate an indigenous knowledge system – and conversely might an indigenous knowledge system guide the governance processes within a blockchain system? Do blockchain-based location technologies accord with IK?

I need to make it clear: There’s nothing wrong with Indigenous Knowledge, Indigenous Governance or Indigenous Knowledge Systems. This research project is not about finding or using technologies to solve problems with IK. This study is interested in how blockchain systems impact Indigenous agency. IK doesn’t need fixing.

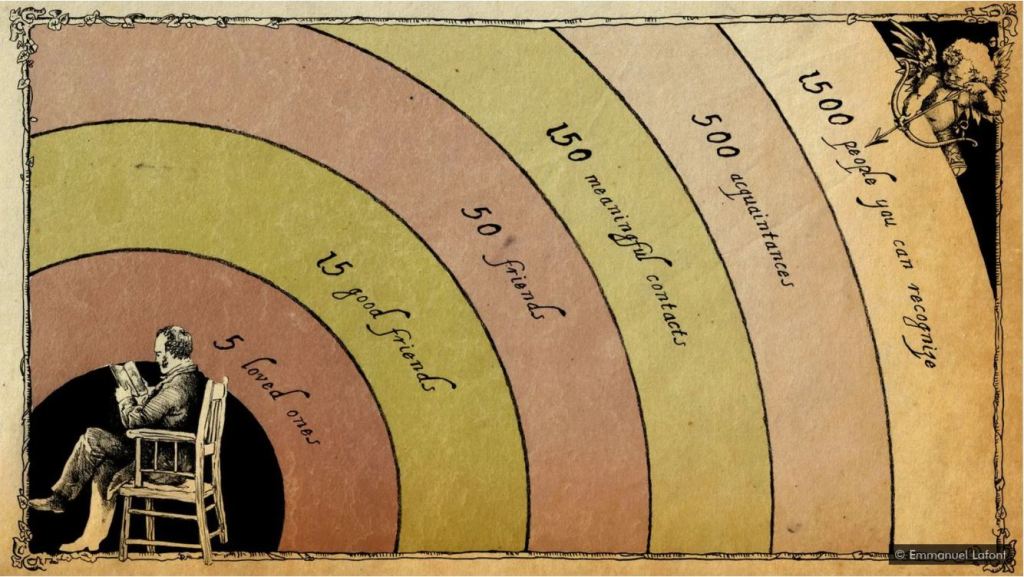

However, IK systems are localised and made for relatively small groups. Arguably, Indigenous governance doesn’t scale beyond a certain number of people – aligning with the Dunbar number suggesting that any network exceeding 150 is unlikely to cohere well or last long before they split off or collapse.

Nick Szabo argues that challenges to social scalability can be overcome with applied computer science – blockchain was invented for that purpose. But IK systems are localised because they are grounded in a law where land is sacred. How does that accord with technologies that rely on resource extraction?

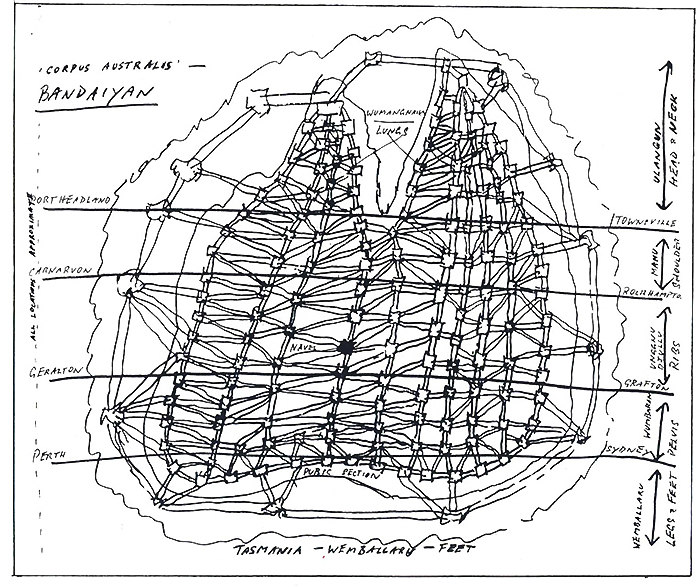

What matters is how groups are syndicated together in an economy. Anderson in Yunkaporta discusses Rainbow Snake Dreaming as a continental common law that governs the way different local systems interact, trade, and maintain integrity of borders. Does syndicated diversity as ceremony answer the challenge of scale in decentralised systems?

Like Wilmott says, Decentralisation is not the same as decolonisation. Whether blockchain is likely to be a mechanism for emancipation of Indigenous peoples in Australia, or whether it may serve in the pursuit of self-determination is yet unclear. And that is what this research project aims to find out.