Understanding self and others within the schema of the worlds around us: maps as an entry point into the analysis of the interaction of European and Aboriginal knowledge systems.

The skills of visualisation and visual analysis are essential to any understanding of the basic theoretical issues of perception and cognition

Turnbull 1993: v

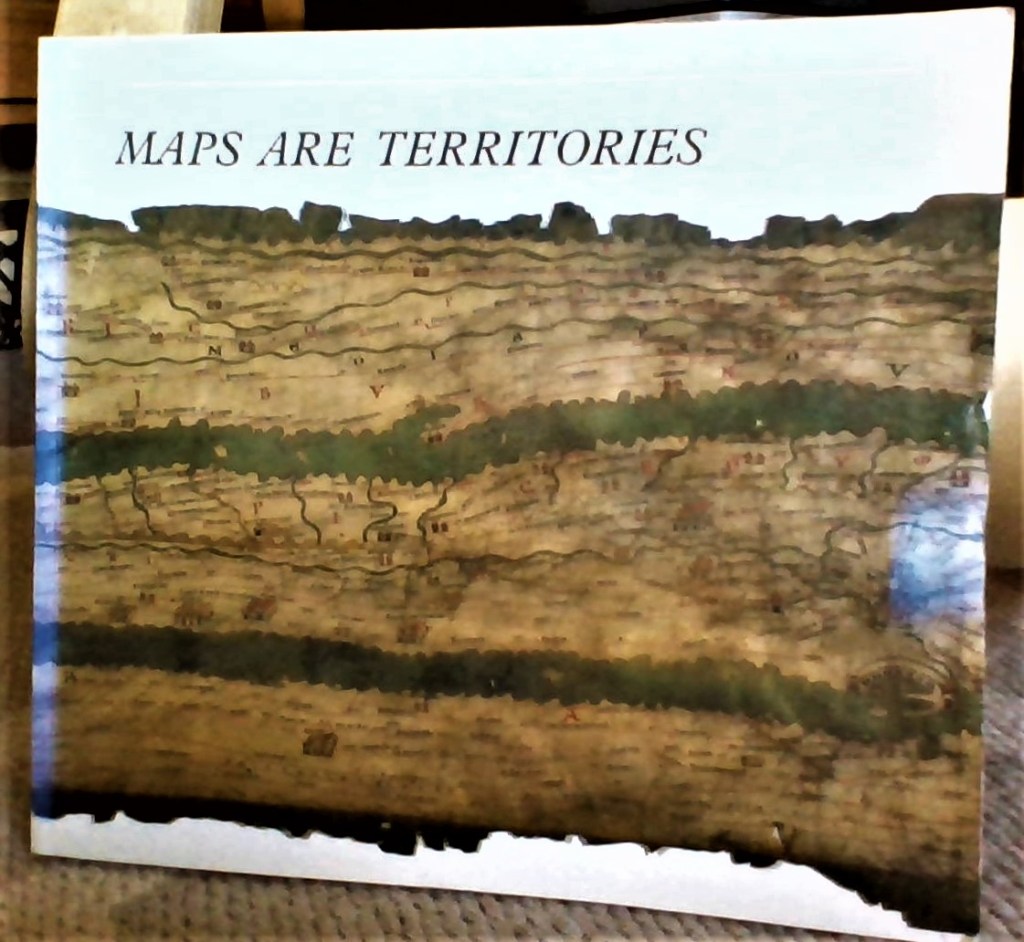

My son has a pesky habit. He stands in front of our bookshelves and, one-by-one, extracts books from the shelf by pulling slowly on the top of the spine with his tiny pointed index finger. Libro remotionem cum digitus, the famed and ancient ritual abhorred by librarians the world over. This ritual served apparently no purpose (to me) other than to give me an extra daily chore and something to mutter about. Until one day, he removed this:

It fell open on the floor, to a page describing Yolgnu knowledge as a commodity. I was spellbound. Not only does it describe the “product” itself, but the knowledge network in which it sits – “the real stuff of interaction between groups, [that] depends for its existence on constant activity… constant negotiation [so] everyone knows who is responsible for what part of the knowledge network, who is charged with the care and maintenance of what song, and what land.”

What is being described is an economy. A knowledge economy; flows and exchanges of knowledge – where the knowledge has value. This economy is about the knowledge of care and maintenance of land – we might call it Country. Rather than read on from that bolt-out-of-the-blue paragraph in the middle of the book, I felt compelled to read from the start of the book, to understand the context in which such a concept would fit – and what it had to do with maps. ?!

This book (which its distinguished author David Turnbull described to me in a phone conversation as being “practically antique”) is all about maps: their theories, their conventions, what sets them apart from mere pictures, which maps are privileged and which maps are discounted, whose knowledge is privileged, whose is discounted. These are not just lines and squiggles describing how to get from A to B. They are instruments of power.

In his analysis of maps as a metaphor for knowledge, Turnbull tells us that space plays a fundamental role in ordering our knowledge and experience of the world (1993). Cognition, in the maturing child, depends on them building an organised schema of the topologies and dimensions of the objects in the space around them (Piaget & Inhelder 1967 cited in Turnbull 1993). What follows is a process of constructing (or learning) a system of signs or symbols that represent that topology: verbal symbols (names) and visual symbols (signs or pictures). This is a process shared and experienced by all humans, and it is something we have done from the dawn of time.

Once hominids had developed names (or other symbols) for places, individuals, and actions, cognitive maps and strategies would provide a basis for production and comprehension of sequences of these symbols … Shared network-like or hierarchical structures, when externalised by the sequences of vocalisations or gestures, may thus have provided the structural foundations of language … In this way, cognitive maps provided the structure necessary to form complex sequences of utterances. Names and plans for their combination then allowed the transmission of symbolic information not only from individual to individual, but also from generation to generation.

Malcolm Lewis 1987 cited in Turnbull 1993 : 2

These cognitive schematics are codified using symbolic information that may comprise aural or graphic elements. The elements, codes, signs, symbols are assigned by humans to the objects being described or represented. The signs chosen are often (but not always) arbitrary, and in order for them to function as a means of expressing ideas or thoughts to describe knowledge of the objects and how they are organised in space, they (the signs) must adhere to ‘a complex set of tacit rules and conventions that have to be learned by practice. … [Therefore, there also has to be] a social community which tacitly accepts these rules and shares an understanding of these conventions’ (Rudwick 1976 cited in Turnbull 1993: 5).

What emerges is a codified system (a language – verbal or visual) reliant on conventions or ‘tacitly accepted rules’ that provides the underpinnings of a model (or theory) of reality – what might otherwise be described as an ontology. In the context of maps, Turnbull illustrates the arbitrary nature of the conventions that are chosen and agreed upon by the given community who will read and use the map as a reference that guides them in their understanding of the natural world to which it refers:

North, whilst being one end of the Earth’s axis of rotation, is not a privileged direction in space, which after all has no ‘up’ or ‘down’. That North is traditionally ‘up’ on maps is the result of a historical process, closely connected with the global rise and economic dominance of northern Europe.

Turnbull 1993: 8

Seemingly, these tacitly accepted rules and conventions are not only arbitrary, they ‘often follow cultural, political, and even ideological interests’, and ‘if [they] are to function properly they must be so well accepted as to be almost invisible … transmitted in a code that by Western standards appears neutral, objective and impersonal, unadorned … and unmediated by the arbitrary interests of individuals or social groups’ (1993: 8-9). It is implicitly assumed that the conventions that govern the creation and interpretation of these representations of reality are ‘given’, part of the ‘existing scheme of things, the invisible, conventional and ‘self-evident patterns of doing things’’ (1993: 10).

These ‘givens’ structure what it is possible to ask and what it is possible to answer. They lay down the criteria for what is to count as knowledge.

Turnbull 1993: 10

But, the conventions are not self-evident. Neither do they represent ‘invariant [characteristics] of the world’ (Turnbull 1993:2). They are a system of signs, historically constructed and deeply entangled with the knowledge and cultural norms of the societies from which they emerge.

Let’s discuss that process somewhere down the track…